-

Robyn

When I first began sharing with friends about our summer travel plans I would mention our intention to tour Auschwitz, the site of one of the darkest series of crimes ever committed against humanity. Although some people were noticeably moved to hear this, I was more often met with furrowed brows and looks of dismay. “Really?” some would ask. Often there were long pauses, followed by a kind of bewilderment and the question “Why?”

“Rick’s Jewish,” I’d say. “And he wants to connect with that part of his ancestry… “and, as a human being,” I’d add, “it’s my ancestry too. It’s important to see it, and to remember these times.” Especially among the New Age crowd of Ubud where we live with its emphasis on positive thinking, courting such shadow realms was sometimes viewed as suspect. We wouldn’t want to attract negativity by focusing on negativity, now would we? But alas, there is more than one pathway for light to pass through a prism.

“Rick’s Jewish?” our friends would sometimes wonder aloud. Most of them did not know this. Rick doesn’t particularly express himself in any way that identifies his Jewish roots, and people are often surprised to learn of it.

A few years ago when we were preparing for a trip to India, I took to the task of completing the applications for our ten-year visas. When filling such forms, I never know what to write in the boxes that require religious affiliation. Is “Breath” an option yet? How about “Nature-worshipping lover of the sentient earth?” Since those choices have not as yet made it onto the official checkboxes, I usually just mark “Other.”

But sometimes I tick the box called “Christian” in a nod to my roots and to my genuine love of Christ, and at other times I mark “Buddhist” as a next-best approximation for my winding 21st century tantric yogic path.

That day, I think I ended up marking my box as ‘Christian’ and Rick’s as ‘Jewish’. When Rick looked over the application later, he suddenly grew alarmed. “Jewish?! No, god, no don’t write that. You don’t write that on forms if you can avoid it.”

You don’t?

Oh darling, I didn’t know that.

Ok, I see now. There’s much more here to be unwound.

We weren’t alone in our desire to visit Auschwitz, to register the horrors with our own two eyes. Between three and eight thousand visitors tour the defunct camps each day. The tours are run with an eerie efficiency, mostly in silence, and at times in single file lines. Almost no one makes a sound at all, save for the well-practiced monologues of the somber tour guides which are piped in through audio headsets in a handful of languages for each small group.

I’d learned the basic history of the Nazi occupation and genocide when I was in high school, and had visited the superbly well-done Holocaust Museum in Washington DC when I was 19. When Rick was still a schoolteacher in the classroom, he taught Holocaust history, so we had some emotional preparation for what the day might entail. But nothing can quite prepare you for walking those grounds yourself, for running your fingers over metal railings or wooden bedposts that hundreds or thousands of prisoners touched not so many years before.

We shared a van with six others for the hour and a half drive from Krakow to the site of the camps. Once everyone was squeezed tightly inside the closed vehicle, three screens dropped from the ceiling and a black and white documentary began to play. For the next 45 minutes, with the windows rolled up and the placid green countryside flashing before us, the silent tension in the van grew thick and prickly. Eight strangers sat together in silence. Our driver, Slawic, through some extraordinary combination of psychic blocking and/or remarkable resilience, listens to this documentary and visits Auschwitz every day. Captive passengers suddenly together on our tour of the terrors of the recent past, we witnessed graphic depictions of starvation, beatings, unthinkable medical experiments, shootings, and the murder and incinerations of thousands of innocent men, women, children, and babies.

1.3 million people entered the camps Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and Auschwitz III Moronow. Upon Soviet liberation, only 7,000 emerged.

Entering Auschwitz I, we came first to the iconic gate inscribed in wrought iron with the words “Arbeit Macht Frei.” Work will set you free. A chilling wave of revulsion rose up my spine. “Work here will break and then kill you” was what it really meant to say.

The summertime landscape here is entirely ordinary; leafy trees, green grass, swallows and sparrows swooping overhead, reminiscent to me of my childhood landscape in rural Minnesota. “This wasn’t long ago in a place far, far away,” an inner voice told

me. “This was yesterday, and could happen anywhere, and in any place you know or have known.”

Our tour guide was a Polish woman in her early forties. Several of her ancestors had suffered and died at Auschwitz. Her tone was serious, intense, and at times trembled with emotion; she had somehow managed to stay open to the pain of this place even though she’s given this same talk countlessly over the fifteen years she’s worked here.

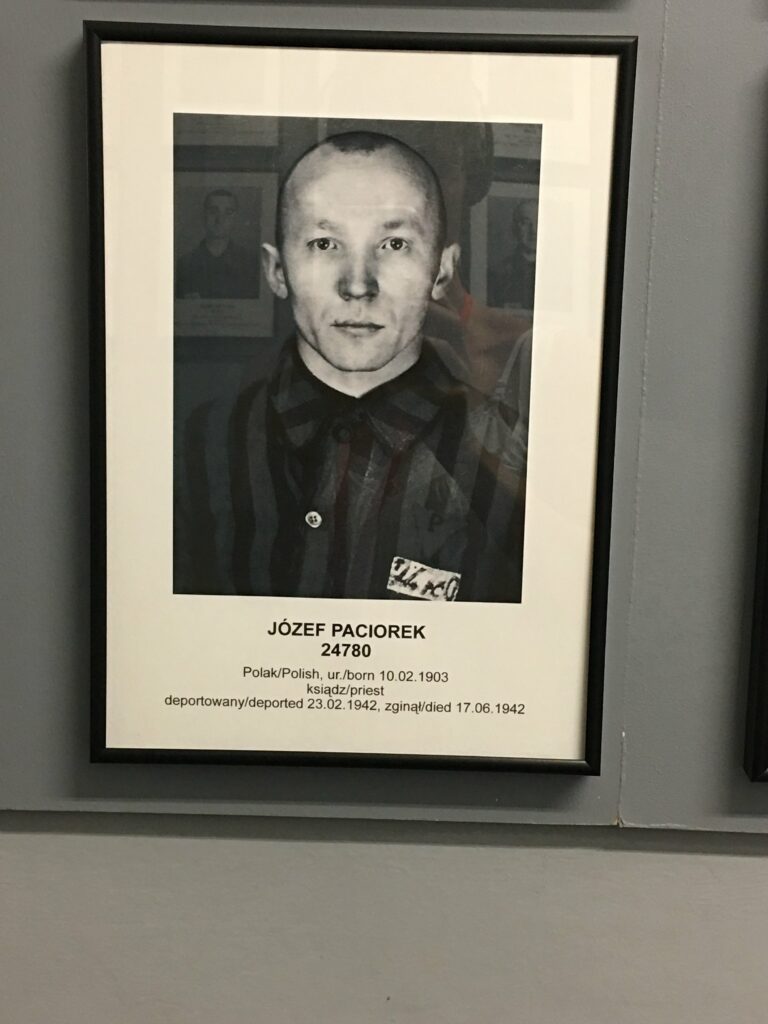

We wound through the uniform brick barracks, each one only slightly but uniquely transformed to showcase some particular aspect of camp life. One of the barracks housed photographs of prisoners and artwork depicting the camp’s inhabitants. Another barracks was a punishment site: cells for solitary confinement, cells for punishment by starvation, and horrific cells for punishment by prolonged standing in tiny vertical brick cells, sometimes 3-4 prisoners to a cell. Each of these sentences had been heaped onto the bodies of innocent people, already breaking under the weight of sickness, degradation, malnutrition, and extreme overwork.

We saw the cell of a Polish priest who had given his life to save another. The man that he saved had a wife and children at home and he hoped, against the odds, one day to return to them. When the guards singled out the family man for punishment, the priest stepped forward and asked if he could take the punishment instead. Baffled and amused, the guards eventually granted the priest his request, and sentenced the priest to death by starvation. We were shown the cell where the priest lived and died, where candles and flowers had recently been left there in his honor. The man whose life the priest had saved turned out to be one of the few survivors of the camp, and upon liberation he returned home and was reunited with his family where he lived out his days. The priest’s sacrifice had not been in vain.

Entering the barracks that housed the innocents’ confiscated possessions, we saw heaping mounds of shoes, many of them in styles that have recently resurfaced and that could easily be seen on the feet of my friends. An ocean of pots, pans, and kettles washed up near a shore of hairbrushes, toothbrushes, and combs.

I’d seen the piles of human hair before at the museum in DC, and remembered being deeply unsettled by it. But here the sheer quantity of hair (just a small fraction of what had been collected) was staggering. Upon arrival at the camps, the prisoners’ hair was systemically shaved, collected, and bagged. What I didn’t know before was that it was then shipped off to Germany to be made into coats, rugs, and blankets, some to be used by Nazi troops.

The plight of animals came to my awareness again and again throughout the day—the factory farmed cattle, pigs, and chickens, even farmed and depleted wild-caught ocean fish. Animals used for fur and leather. “They are no different,” a voice within said to me. “Their unthinkable treatment is no different than the horror of this.”

Of course, this is not to equate the value of the inmates to that of animals, as the Nazi regime did. This voice seemed to come to me instead as a way to help me to raise the value of animal life as equal to that of humans. There are holocausts of different kinds continuing around us today.

As I walked through the grounds and corridors, first through the smaller Auschwitz I, and then across the sprawling, clear-cut flatlands of Auschwitz II-Birkenau, I experienced something that I can only describe as entering an altered state. It began with a steadiness that had my legs and feet feel as though they extended far below me into the earth. My mind grew exceptionally still, open, and focused. My awareness spread wide, my sense of smell, hearing, and the sensitivity of my skin grew acute. Grounded and expanded, a gentle light streamed through my body. My hands, feet and chest radiated as if they were glowing. These energetics were somewhat familiar to me, similar to what I often experience when I work with clients in session, when I open my energy body for the purpose of transforming or empowering a certain situation. But here I didn’t ask for it or intend it, it simply happened.

Over and over, these words came to me in endless repetition throughout the four-hour tour:

I Love You.

I’m Sorry.

Love is Real.

It Ends.

At intervals, Rick and I listened to the tour guide’s amplified oration through headphones in one ear and a recording of a Jewish prayer, the Mourner’s Kaddish, through a separate set of headphones in the other ear.

At the break, he and I spoke to each other for the first time since the tour began. I told Rick that phrases were coming to me over and over again, that I felt I needed to speak them internally as I walked.

“Me too,” he said. “I received words to say, too…” he said as he began to tear up. “Mine are slightly different.”

This happened.

It is over.

We are safe now.

As we toured Auschwitz II-Birkenau, time collapsed within me in its own mysterious way. In my inner eye I was shown the permeability of time, where the frames of ordinary reality softened a little. From here I could see that when viewed from a certain vantage point, all events occur singularly, at once. I could see that who and how I was being in this present moment was having an impact on those who endured and perished in the camps, however large or small that impact might be. As I saw this, I began to lightly touch any surfaces where it was permitted: the walls, the railings, the brick and crumbling mortar that had been hastily laid, the smooth worn wooden beams that framed the three-tiered bunk beds.

As I touched, I said internally the words “I Love You” as I allowed the full force of that Love stream through me, letting the light move and flow through the subtle body channels that have opened in this lifetime, whether by grace, by practice, or by the love of another.

“It Ends,” I said like a chant muttered within as I ran my finger along the windowsill that looked out from the end of barracks bunk. “It Ends,” I left this message like a love note, sent through whatever time-space portal I had entered, hoping it might be received and experienced as a moment of reprieve, a brief window of light, for any whose hands touched the same place where my hands touched now.

I will not write much today about what it was like to enter the gas chamber where thousands perished upon forced inhalation of the engineered pesticide Zyclon B. I don’t know how to say what it was to see, in the underground room next door, the four small ovens where prisoners who still lived were forced to shovel the dead bodies of their kin into the flames.

I can only say that I was chilled to a point of utter stillness inside, and that to stand on the ground of such hell made me first grow cold and to weep, and then to experience a narrowing focus and alert insistence where the words “never again” burned in my mind.

***

The trees were good and necessary companions that day. Several times over, we both doffed our sandals and stood barefoot on the grass, leaning into the comforting roughness of tree bark, connecting our bodies with the bodies of the trees and the larger body of the breathing earth. Once connected to this greater field of intelligence, I found I was more able to feel and receive the deeply imprinted and echoing trauma of this place, and to give it space to begin to be embraced and integrated within me, contributing to my own understanding of the darkest shadows of the human race.

***

It wasn’t easy to visit this place that once knew so much horror and pain, even now in the comfort and safety we shared. But I’m glad that I did. It helped me know myself, and know humanity more deeply.

I walked away from Auschwitz knowing this: I am both a prisoner and a Nazi. I am the mother who lost first her child and then her own weary and grizzled life, and I am the commandant’s wife. I am not immune to being the victim of such crimes, nor am I immune to enacting them. While “never again” is what we might all want in our hearts, “already now” may prove to be a more useful mantra over time. Already now the seeds of oppression and victimization live among us, and within me. Already now is where only difference can be made.